General Hugh L. Scott: A Life in Three Acts

What can a forgotten soldier tell us about modern war and the U.S. rise to power?

My great-grandmother was born in 1888, the year Carl Benz received the world’s first driver’s license as he began to sell its first commercially viable automobile. She died a little past her 100th birthday in 1988, when the crew of the Space Shuttle Discovery experimented on red blood cells in orbit and the National Science Foundation laid the first transoceanic Internet cable.1

These latter developments were probably not on her radar. She had canceled her newspaper subscriptions at some point in her late nineties, having “seen enough.” (She remained a devout watcher of Phil Donahue, however — if only to torment her mortified sons by asking them to elaborate on some of his more risqué programs.) But what an extraordinary amount she saw from her vantage point even in a small town in Western Pennsylvania: the Great War, the Great Depression, World War II, the invention of the television, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and, yes, the leap from the horse-and-buggy to manned space flight. If “there are decades where nothing happens, and weeks where decades happen” there are centuries where the leaps must feel far vaster and more volatile than a hundred years.2

I have long been fascinated by individual lives that bridge eras and paradigms — especially those who stood with one foot in the nineteenth century and one in the twentieth. From their vantage point athwart history, they expose how our understanding of the world and its possibilities are provisional, ripe for disruption and filled with misconceptions. They also demonstrate continuities in how we think about problems. And sometimes, they show that people are more exceptional and more capable of adaptation than meets the eye — even if they sometimes come up short.

Act I: From Indian Country to the Pacific Empire

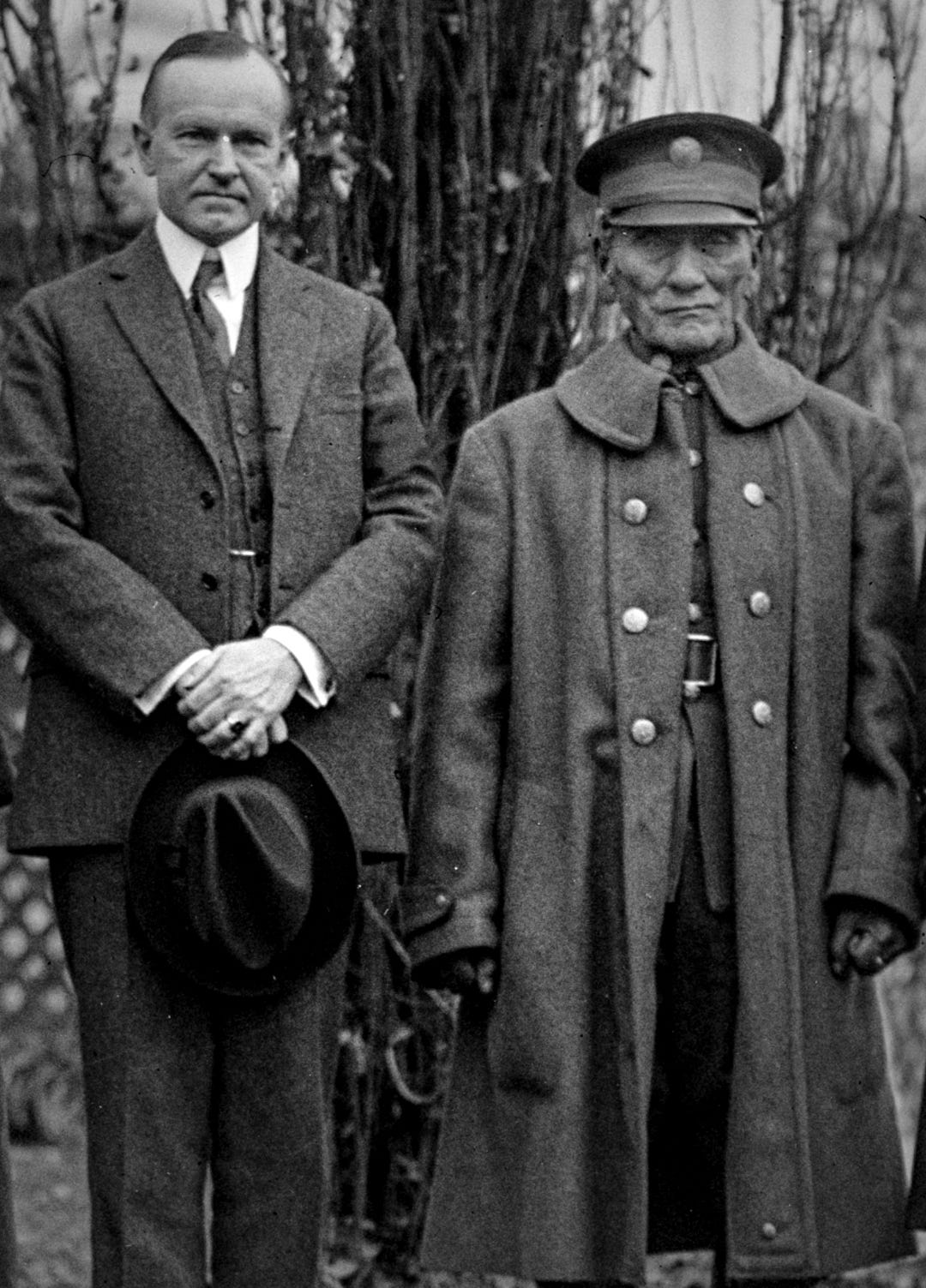

This leads me to Hugh Lenox Scott (1853-1934), who served as the seventh chief of staff of the U.S. Army from 1914 to 1917 and plays a minor role in my research due to his service on the Root Mission to Russia.

Despite his service as one of the most senior officers of his era, Scott is a decidedly minor character in the annals of U.S. military history. Overshadowed by the exploits of John Pershing and the cadre of junior officers he mentored, from George Marshall and Douglas MacArthur to Dwight Eisenhower and George Patton, Scott rates a single mention related to his work to establish a summer training camp for reserve officers in WWI in one of the major histories of the U.S. military.

And yet, when diving into his papers at the Library of Congress, one is immediately struck by the breadth of the man’s life and how disorienting his times must have been.

Scott received his commission at West Point in 1876, beginning his career as a cavalry officer. He entered the Army as it contracted from its May 1865 peak of over 1 million men to its authorized maximum strength of 27,442 in the year he graduated. Its central preoccupations were the so-called Indian Wars, sparked by rapidly expanding white settlement and treaty violations that led to the devastating confinement of Native Americans to reservations and enforced “civilization” against which they rebelled.

Assigned to the 7th Cavalry, one of Scott’s first tasks was to travel to Little Bighorn to mark the locations where Custer’s troopers had fallen in battle against the coalition of Plains tribes led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. Stationed on the frontier in one fashion or another for over twenty years, his experiences and attitudes were both typical of the era and idiosyncratic.

In the almost unfathomable 16 years it took for him to advance from first lieutenant to captain, he pursued the Sioux and Nez Percé and never doubted the basic rightness of the U.S. Army’s position despite the punitive nature of these campaigns. He also developed a respect for Native American culture, a preference for de-escalating conflict wherever possible, and commanded a unit of Native America scouts. Years later

His friendship with I-See-O (also known as Tabonemah), who served as his first sergeant, was particularly pivotal and unique. The Kiowa soldier worked with Scott to defuse a war between Native American tribes during the “Ghost Dance” movement and taught him Plains Sign Language, used by the tribes to communicate across language barriers, to the point where Scott was seconded to the Smithsonian to write a book on the subject and tribal ethnography.

As biographer Armand La Potin notes, Scott had evolved into a “frontier diplomat” — skills that were put to use in the wake of the War of 1898 during the occupation of Cuba and the Sulu Archipelago in the Philippines and in negotiations with Pancho Villa, whom he befriended during the Mexican Revolution in an effort to balance the various rebel factions in that country’s civil war. As he puts it in his autobiography:

It requires patience to listen all day in the tropical heat to a succession of empty speeches. Each one however, was entitled to his day in court and I saw that he got it… They use up their power in talk; when they say something they feel like they have actually done something and their desire for action is satisfied. When negotiating with armed and angry Indians[,] I am never anxious over the voluminous talker, but I watch the silent one in the corner. His desire for action is not dissipated in talk, and he may act. When they talk out their opposition, there is no power of resistance left, and they must fall like ripe fruit in your hands. I have seen this happen times without number, not only in Cuba, but in Mexico, in the Philippines, on the Plains of the West. One only needs an unfailing and sympathetic courtesy and an unconquerable patience. If you have not these qualities try for some other business, for diplomacy is not for you.

Such passages can be read as a sign of Scott’s clear interest in other cultures and preference to avoid violence if possible as well as the basic paternalistic attitude of the era. It can also be read in light of the broader thrust U.S. policy at a time of imperial expansion. As the historian Katharine Bjork argues in a recent book, one can read Scott’s career as a ligament connecting the experience of wars in “Indian Country” to the broader story of the American empire that grew up in the wake of the Spanish-American War of 1898.

Act II: From the Root Reforms to the Draft

Yet Hugh Lenox Scott’s colorful military career cannot be defined purely in terms of these assignments, as interesting as they are. He lived well into the twentieth century, rising to lead the U.S. Army as America entered a very different kind of war in 1917, one that would reshape the world and the institutions which shaped him.

After a stint as Superintendent of West Point (1906-1910) and service on the border during the Mexican Revolution, Scott returned to Washington in April 1914 at a particularly contentious moment.

The Spanish-American War revealed that the Army had a low state of readiness for an overseas war. Secretary of War Elihu Root embarked upon a series of reforms to ensure that the service was better prepared for war. One of the most important measures created the chief of staff of the Army and the Army Staff, downgrading the role of the powerful but parochial Army bureaus which managed administration, training, weapons production, and procurement and had powerful backers in Congress. Leonard Wood, Scott’s commanding officer during the occupation of Cuba, rose to chief of staff and vigorously supported the reforms.

Now a major general at age 61, Scott followed in Wood’s footsteps, becoming chief of staff himself in late November 1914 as it became clear that the war in Europe wasn’t going to end by Christmas.

Scott’s peers were harshly critical of his leadership. As La Potin chronicles, former President Taft declared that he was “wood in the middle of the head.” An officer referred to him as “over the hill” and claimed that Scott “preferred to talk in grunts” and “went to sleept in his chair while transacting official business.” Wood himself said his former subordinate was “dull and stupid” and had “dropped off about eighty percent in efficiency since he was with me in Cuba.” Reading these comments, one pictures an aging man out of his depth, more familiar with life in the saddle, canvas tents, and an on-base officer’s club than survival in the bureaucratic battles of Washington, DC.

There is undoubtedly some truth to this portrait of this elderly officer, but it is not the whole story. Scott inherited an organization which had not fully transitioned to its new form. The polarizing Wood had inadvertently poisoned the well for his successors by getting into a brawl with Congress over firing the popular officer who led the powerful Record and Pensions Division. Congress retaliated through an appropriations bill that cut the size of the general staff, which required the intervention by Root — now a U.S. Senator — to kill the offending provision. Scott embraced an indirect approach to reform, asserting the chief of staff’s prerogatives to review the bureaus’ work but taking a more conciliatory interpersonal approach.

More importantly as the specter of war loomed, he had an army to raise and mobilize — a process that the United States government had not embarked upon in any serious way since the 1860s.

Accounts vary on who was most responsible for the implementation of the draft, with John Whiteclay Chambers’ To Raise an Army3 being perhaps the most authoritative:

President Woodrow Wilson made the final call to proceed with selective service in March 1917, in part because of Theodore Roosevelt’s public desire to raise volunteers to fight — a proposal which threatened to politicize the army, disrupt an orderly call up, and aggrandize Wilson’s rival.

Roosevelt and Wood were vocal advocates for military preparedness, with the latter creating the summer training camps for college students that would eventually evolve into ROTC.

Judge Advocate General Enoch Crowder was the principal author of the Selective Service Act and Captain Hugh Johnson (later a member of FDR’s “brain trust” and director of the National Recovery Administration) shepherded it through Congress.

But Scott’s forceful internal advocacy, which pre-dated Crowder’s embrace of conscription, is notable. Drawing on his experience training soldiers and observing state militias lacking in readiness, he argued against a call-up of poor quality units and for a much broader effort which he believed would help citizens recognize their obligations to protect the country and serve “as the exponents of democracy that should regenerate the political systems of the world.” In Scott’s eyes, conscription — and the Army — were part of an American moral mission at home and abroad, one we can hear echoes of today in advocacy for compulsory national service in and out of the military.

Furthermore, Scott found the man to lead that Army in the field, elevating John Pershing to command in Mexico to pursue his old interlocutor Pancho Villa. From that billet, Wilson would elevate him to lead the American Expeditionary Force in France. It was an inspired choice. That these efforts were basically successful suggests that Scott’s critics had underestimated a man who could make the leap from frontier wars and colonial administration to modern warfare and bureaucratic leadership — even if these were not his métier.

Act III: The Root Mission to Russia in 1917

Hugh Lenox Scott’s third act, however, is perhaps the most striking because it relates to exactly the type of major conventional modern war that the draft necessitated and that was extremely remote from his personal military experience, which consisted of what we might call “low-intensity” conflict today: punitive expeditions, constabulary actions, and counterinsurgency.

Like several other late nineteenth and early twentieth century conflicts, the American Civil War anticipated World War I. Its broad mobilization of manpower, industry, and technology including the railway, telegraph, and modern rifle are all well known as are the tactics of economic embargo. Trench networks surrounded Petersburg on the approach to Richmond in 1864. Casualties were extremely high, though still largely concentrated among soldiers rather than civilians. This was the kind of war that raged in Europe from 1914 to 1918 (and beyond) at orders of higher magnitude.

Yet it was precisely that war that Scott was sent to assess on the Eastern Front in an early and aborted episode of modern U.S. military assistance to a faltering partner.

The tsar had been overthrown in the February Revolution and replaced by the democratic Provisional Government, a development welcomed by Americans who were relieved that they would not have to fight alongside an autocratic ally in the Great War. Yet Russia’s position against Germany was relatively weak in 1917, having lost hundreds of thousands of soldiers in the successful but Pyrrhic victory of the Brusilov offensive a year earlier.

President Wilson asked now Republican elder statesman and original foreign policy “wise man” Elihu Root to lead a mission to Russia to assess the political and military situation and bolster Russian resolve against Germany. He also personally selected Scott to join the delegation, a remarkable decision given that the United States had just declared war but one made to signify the importance of the mission.

Rounded out by others such as businessman and diplomat Charles R. Crane, Cyrus McCormick of the International Harvester Company, YMCA president John Mott, Rear Admiral James Glennon, banker Samuel Bertron, James Duncan of the American Federation of Labor, and Socialist Party journalist-politician James Edward Russell, the Mission was an eclectic group with a fact-finding mandate and a secondary mission to bolster Russian morale, but emphatically not one to offer any promises.

This rather remarkable group left Washington in May 1917, traveling across the Pacific to Vladivostock and traveling across China and Siberia to Petrograd via train. After meeting with members of Alexander Kerensky’s government, some members of the mission dispersed to conduct assessments in their areas of expertise.

Scott and his aides met with Russian generals and traveled to the front, assessing requirements of materiel and the state of Russia’s forces. He had departed the United States perhaps more pessimistic about the Provisional Government’s military prospects than any of his companions, speculating that “it looks very much as if Russia is breaking up and we will be too late” as Russia’s army had been “crushed.” What he found generally confirmed his pessimism: namely, a chaotic political situation and hundreds of thousands of soldiers away from the front — including men riding the rails in the opposite direction as he crossed Russia.

This changed at Mogilev in present-day Belarus, where he witnessed a successful combined arms assault against the Austrians on the Galician front on July 15 and met General Lavr Kornilov, who later attempted a confused coup against the government in September. These encounters deeply impressed him, but remain a cautionary tale in the annals of assessing foreign militaries.

The Kerensky Offensive, partially timed by Kerensky for the the Allies (and the Root Mission’s) benefit, was intense but its gains were short-lived and easily reversed — not an uncommon occurrence in the maneuvers late in World War I. In this case, they ended when Germans came in to reinforce the Austrians, driving the Russians back. Scott lost touch with the operational situation in July, leaving to assess military aid requirements in Romania just a few days later, and that he was so quickly swayed suggests the problems of offering assessments based on fragmentary encounters.

Nonetheless, Scott had a better grip of the fundamental problems facing the Russian military than many historians credit and was hardly insensible to the challenges of attritional warfare.4 In his final report to the Secretary of War six weeks later, he noted that manpower and logistics were the most severe deficiencies for the Russians. He estimated between 1 million and 1.5 million deserters and noted a shortage of trains to bring soldiers to the front. He also correctly noted that keeping the Russian front open would ease the defeat of the Central Powers, arguing that it would be worth “a great sum of money to keep Russia even passively in the war… for the dangers attending her withdrawal are too great for any haggling to be admitted.”

Overawed by the Kerensky Offensive, Scott naïvely hoped that the success he briefly saw in Galicia indicated momentum, improved morale, and Petrograd’s solid political control over Russian forces. That virtually none of this proved to be the case — and that Scott’s initial instincts and top-level diagnosis were essentially correct — suggests less a man completely out of his depth than one who failed to update his assumptions (unspoken or otherwise) in a rapidly evolving situation — common failings, especially as we grow older.

This is a problem that is still with us in understanding wars, as we see in what Neil Hauer refers to as the “war of narratives” in Ukraine. It is tempting to extrapolate that sudden reversals on the battlefield — especially when our starting expectations are low — will inexorably shift to long-term trends, unmoored from operational realities. Scott and other members of the Root Commission fell victim to this temptation, despite their other accomplishments.

Coda: Retirement and Reflections

After returning to the United States and stepping down as chief of staff, Scott finally retired from the Army and settled in Princeton, where he had family roots. He passed his later years on the Board of Indian Commissioners, resuming his research on Native American culture and sign languages, and serving on the New Jersey Highway Commission before dying in 1934. It was a fitting coda to an unusual career that began with finding Custer’s bones on horseback and ended deep into the twentieth century as cars and airplanes crossed the country.

Scott may be ultimately a minor character: in the annals of American history, the evolution of the U.S. military, and in my own work. But his story offers an opportunity for us to take stock about where our own lives start, where they might end, and our struggles to comprehend what we see along the way.

The Internet was, in fact, “a series of tubes.”

This quotation, often attributed to Vladimir Lenin, is almost too good to factcheck. But the source appears to be an 1863 letter from Karl Marx to Friedrich Engels: “Only your small-minded German philistine who measures world history by the ell [a unit of measurement for cloth] and by what he happens to think are ‘interesting news items’, could regard 20 years as more than a day where major developments of this kind are concerned, though these may be again succeeded by days into which 20 years are compressed.”

Chambers, a student of the great New Deal and FDR historian William E. Leuchtenberg, dissects the political and bureaucratic debate over the draft in agonizing detail. The inadequacy of a purely volunteer Army became increasingly clear to Wilson, Secretary of War Newton Baker, Scott, and the General Staff. Yet the politics of conscription were difficult, especially within Wilson’s Democratic Party. Its large Southern agrarian wing wanted agricultural workers to excluded as essential to the war effort and assurances that there would be no integrated units. One Southern senator even sought specific concessions aimed at keeping African Americans working in the cotton fields. The haggling between interest groups produced “selective service” rather than a general call-up, though Chambers argues that on balance this is “best understood as a victory for the values of a cosmopolitan urban-industrial elite over rural-agrarian traditions.”

For instance, Alton E. Ingram’s dissertation “The Root Mission to Russia, 1917” offers a comprehensive account of the trip and generally concurs that the members of the Root Mission failed to comprehend what they saw, concluding that Scott as “totally incapable of understanding the Russian military situation” which is at odds with some of his own observations.

With the current hype around AI, it’s easy to feel that there’s something special or unique about the transformation we’re going through as a society right now. Thanks for the reminder that societal and technological change was experienced and dealt with by people long before us, and there’s things we can learn from those who didn’t make it into most history books.