2024: The Unspoken Assumptions

How History and Policy Depend on Knowing What We Don't Write Down

At the beginning of every new year, ambitious resolutions are easy to set and even easier to abandon. For that reason, I’ve often found making predictions about current events in the new year and then re-examining them at year’s end much more rewarding. Beyond simply avoiding demoralization (“I didn’t finish reading 100 books / going to the gym four times a week / finishing that novel this year”), it can also help us re-examine our implicit theories of how the world works – especially when we’re proven wrong.

Surfacing those implicit theories can be a surprisingly difficult task since we are all prone to hindsight bias and soft revisionism, as Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner have shown. But they can also be difficult to surface because we rarely state our theories of how the world works out loud or put them down in writing. And even when we do, there are still truths we take to be so basic and are so ingrained in our way of thinking that they go unsaid.

Reading Between the Lines in 1914

What we take as given but leave unstated has been much on my mind as we start 2024, a year likely to be as volatile as 2023 if not more so. Encountering a brilliant decades-old lecture by the British historian James Joll entitled “1914: The Unspoken Assumptions” by way of recent essays by Ben Rhode of the International Institute for Strategic Studies and my colleague Frank Gavin has certainly helped.[1]

Joll, who wrote the introduction to the first English edition of the German historian Fritz Fischer’s controversial Germany’s Aims in the First World War in 1967, was deeply familiar with the documentary evidence of the July Crisis and the multitude of arguments about “war guilt” that had raged even before the Treaty of Versailles. Armed with the memoranda, war plans, and diplomatic correspondence furnished by various government and private archives, generations of historians and political scientists had meticulously reconstructed the years and weeks leading up to the outbreak of hostilities on July 28.

Yet, as Joll argues in his 1968 meditation, the account of events was insufficient to settle the question of why Europe went to war. Fischer could usefully advance the historiographical debate by pointing to new pieces of evidence: most famously, a chancellery memo that sketched expansive German war aims (the so-called “September Program”) which he argued showed that Germany had sought war for territorial expansion. But was that memo actual policy reflecting a longstanding drive by the Second Reich for dominance or merely a working document, batting around a maximalist negotiating position before the Battle of the Marne had become a morass?

The answer is not in what was written, but rather “in the minds of Germany’s rulers” and their actions have to be judged based on what the historian can reconstruct of their thoughts.

Joll dwells upon the role of “the unspoken assumptions” in the conduct of statecraft because he recognized that “one of the limitations of documentary evidence is that few people bother to write down, especially in moments of crisis, things which they take for granted.” We have to look elsewhere to understand how people believe the world actually works (beliefs about the innate “laws” that govern it) and how it should work (motives, mores, and ethical codes underpinning human conduct) — and interrogate how those beliefs inform their choices. The point isn’t that these ideas were never spoken aloud per se, but rather that they have to be inferred and unthreaded from contexts that are often quite alien to us today – and that these unspoken assumptions are rarely spelled out explicitly in the moment.

The historian and analyst of foreign policy, Joll argues, would better appreciate how leaders arrived at their decisions if they understood the invisible but heavy waters they swam through and breathed in. To cite but a few of Joll’s examples:

The British foreign minister Edward Grey’s belief that London could not renege on a non-binding commitment to defend France owed a great deal to the code of “fair play” he learned as a public school boy at Winchester College and the code of the English gentleman — a fact well understood by his French interlocutors.

Numerous Germans, from Moltke the Younger to the “September Program” author Kurt Riezler, as well as Englishmen like Lord Milner, had absorbed currents of social Darwinism that assumed states, civilizations, and “national races” were organic forces locked into a zero-sum competition for survival that made war either inevitable or highly likely — and possibly even desirable.

Revolutionaries of all kinds embraced bastardized versions of Nietzsche and, in the case of Gavrilo Princip, could even recite snippets of his work that venerated an almost nihilistic drive to create a new order through destruction and assertions of will.

Tsar Nicholas II’s belief that he was merely following the inscrutable will of God as the fatherly leader of the Russian people during many of the crises that defined his reign encouraged a passivity during the July Crisis when Russia’s decisions were critical.

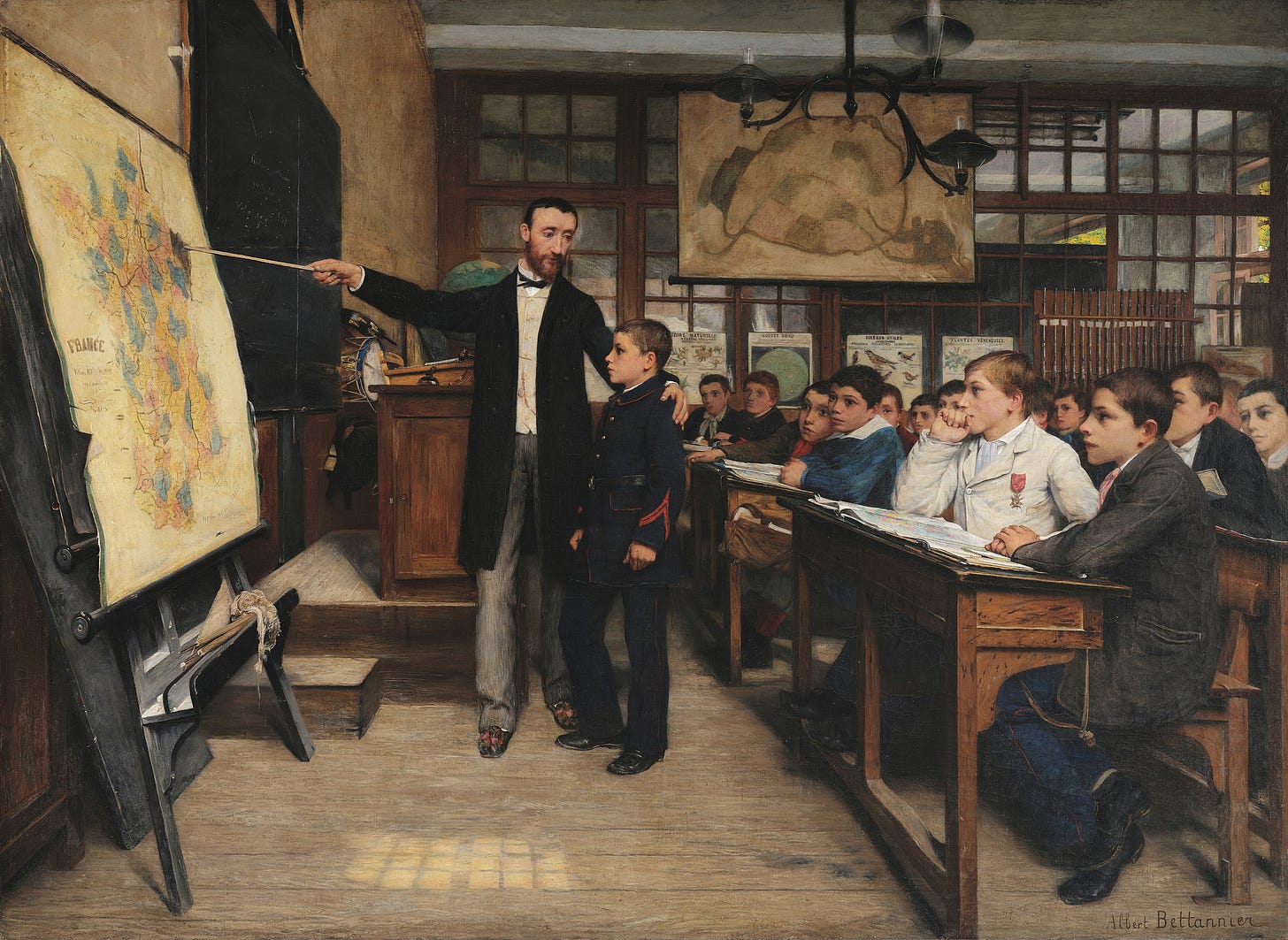

Joll observes that the reconstruction of these views is essential to understanding policy decisions but often difficult to do and points us towards less conventional sources to surface them. He specifically suggests that the role of school systems in forming basic codes of behavior and the popularization of ideas via middlebrow literature which trickles down from ivory towers and professional guilds to political leaders and citizens are especially important. (One can imagine that non-fiction “airport books” favored by business travelers would make for a particularly useful study today.)[2]

Challenges in Reading Between the Lines Today

Whether one is a historian, a policymaker, or a citizen, the effort to surface such “unspoken assumptions” remains incredibly valuable – both as a means of understanding events, gauging one’s own biases while developing strategy, and judging decisions and the people who make them. Yet it remains incredibly hard, particularly when you are merely trying to understand and respond to the press of events — the cascade of “one damned thing after another.” Unlike in 1914 or 1968, however, we face different problems both in our efforts to reconstruct the past and to evaluate decisions in the present.

Historians are lucky when their subjects are like Lord Grey, who was quite loquacious about his school days and its implicit impact on his worldview, or Riezler, who authored a book on international politics under a pseudonym while working for Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg.

In my own work, which focuses on the U.S. strategic imagination and critical foreign policy decisions towards Russia from 1900 to 1933, I benefit from embarrassment of riches: most of my protagonists were prolific writers who read widely, wrote works of history, kept diaries, and maintained extensive correspondence, from Theodore Roosevelt, John Hay, and Charles Evans Hughes and Henry Cabot Lodge, Sr. to Woodrow Wilson, Elihu Root, William Borah, and Loy Henderson. Knowing that Lodge completed a PhD dissertation in History on Anglo-Saxon land law and traveled to Russia with Henry Adams in 1900 surfaces innate beliefs about civilizational development that can be hard discern in hearing transcripts. Hughes’ and Root’s legal careers shed important light on how they approached the sanctity of property rights and under what conditions revolutionary governments were “legitimate.”

This is both true and not so true today. In an era when important government deliberations are reportedly conducted via WhatsApp and keeping journals has fallen out of fashion, crucial records are often inaccessible or simply do not exist. On the other hand, the embarrassment of riches generated by the advent of e-mail alone is staggering. Despite the proliferation of digital records, optical character recognition, database software, search tools, and AI, sifting through and interpreting extant material can be almost overwhelming.

For policymakers, the problems are related but even more perilous. Leaving contemporary records of one’s thoughts can politically and personally dangerous in an era of hacking, leaks, and data dumps of everything from private correspondence and working papers to classified documents, hence the retreat to encrypted apps and private conversations.

Furthermore, surfacing and interrogating one’s assumptions is always an inherently difficult process. “Life is lived forwards and understood backwards” as Kierkegaard put it. We often don’t have time to process or untangle our own experiences until years later, an experience compounded in government where information is compartmentalized across multiple organizations and competing perspectives. And of course, there are also abundant professional reasons to justify one’s decisions and worldview both in media res and in retrospect.

Finally, if it was difficult for policymakers in 1914, communicating at the speed of the telegraph and telephone, imagine the world of 2024, when the crush of events, flood of e-mail, and proliferation of meetings erodes attention spans and makes it even more difficult to reflect and step back in a crisis. At a certain point, one can forgive the action officer at the Pentagon, the State Department, or the National Security Council for simply getting on with the job.

After all, surfacing unspoken assumptions does not necessarily guarantee that you will be able to open up alternative paths to policy success. At times, doing so may not even have much bearing on the decisions that have to be made or do much to convince the parties concerned that they need to change course. Even if Grey had realized that his upbringing had shaped a code of honor that demanded backing France in 1914 – not an inevitable decision, as Joll reminds us, since other members of his party and the government did not support it – it is not necessarily clear that he would have been able to break off the track than Nicholas II with his intimations of fate would have been.

The Melancholy Dane spends most of Hamlet contemplating whether to avenge his father by killing Claudius but interrogating his own motives, beliefs, morality, and mortality at great length simply immiserates those around him and produces an overdetermined result.

The Necessity of Articulating “Unspoken Assumptions”

Yet as Frank Gavin suggests in his essay, unpacking our unspoken assumptions does not have to be an exercise in futility for the policymaker. It can serve as both a cautionary tale and a means of seeing new possibilities.

Frank invokes an experience from early in his academic career at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at UT-Austin in 2000, teaching LBJ’s decision to escalate in Vietnam in 1964-65 to students who were baffled by how obviously intelligent people could commit one of the classic blunders of U.S. foreign policy. Indeed, the decision to escalate viewed from hindsight is hard to fathom if you do not reckon with unspoken assumptions: the widely shared belief that the Third World was a central front in the Cold War, LBJ’s memories of the Democrats being trounced in the 1950s for “losing China,” and his fears of being emasculated if he were to back down to name just three. (Fredrik Logevall’s Choosing War – perhaps the best book I read in graduate school on Vietnam – memorably captures the role and force of these assumptions.)[3]

Noting that the lessons of Vietnam did nothing to prevent another blunder in the invasion of Iraq in 2003 (itself a product of crisis and unspoken assumptions about Saddam Hussein and his regime, WMD and the reliability of intelligence, U.S. military power, and the state of Iraqi society), Frank suggests that:

History’s true power may be to remind us that people once understood their world much differently and carried far different, often hidden, shared assumptions, and that our own beliefs and shared assumptions, often unexplored and unchallenged, may lead to similar catastrophes that will one day puzzle our grandchildren.

That LBJ could simultaneously commit the United States to Vietnam while embarking upon cooperation with the Soviets on smallpox eradication and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, or that George W. Bush could launch PEPFAR and save an estimated 25 million people in Africa from HIV/AIDS even as he invaded Iraq, suggests to Frank that we can both be prisoners of our unspoken assumptions and potentially liberate ourselves from them. All of this is to say that it’s important to recognize that policymakers all have “unspoken assumptions,” to question them, and to unpack when they do and don’t apply.

We have seen plenty of examples of the “unspoken assumptions” in recent few years, both in the United States and elsewhere. Consider Russia and Ukraine. As Rhode observes, many Western political leaders and foreign policy analysts prided themselves on their understanding of Putin and his inner circle as canny political actors seeking to extract concessions rather than risk actual war. The sophisticated point of view during the debate over whether to provide “lethal assistance” to Ukraine after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the beginning of the war in the Donbas in 2014 was that this would be needlessly escalatory and that the Russians maintained “escalation dominance”: the ability, by dint of geography and will, to raise the stakes in ways that would be unacceptable to the West.

To be fair to those who believed both of these propositions, the end to that story has yet to be written. And context matters: a lot has happened since 2014 and much more will happen in 2024. But both Putin’s decision to attempt a full invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, influenced by deeply embedded beliefs about the nature of Ukrainian society and its relationship to Russia, and the West’s provision of incredible levels of lethal aid and assistance to Ukraine without expanding the war suggest that these unspoken assumptions were wrong.

Seeking the Unspoken Assumptions of 2024

Such experiences should make us examine our assumptions and those of our adversaries with greater intentionality, not merely to keep score but to keep one another honest — and maybe improve the quality of policy decisions and historical understanding.

On that note, I propose three distinct ways of tracing our unspoken assumptions so as 2024 begins in earnest.

First, it’s important to articulate our assumptions about the logic of events. As my colleague Hal Brands wrote in a different context where concerns over escalation also came into play, and as numerous current and former policymakers have observed, whether one views international politics as being defined by the “spiral model” or the “deterrence model” of conflict matters. You’ll never hear those terms invoked in the Situation Room – nor should you, since invoking them would be an act of insufferable pedantry – but most people have an implicit theory of the case whether they’ve studied international relations and diplomatic history or not. To grossly simplify: on balance, President Obama appears to have been a believer in the “spiral model,” where pursuing greater security through seeking military advantages leads to fearful adversaries to build up correspondingly — thus decreasing security overall. Others, such as presidents Reagan, George W. Bush, and Trump appear to have been believers on balance in the “deterrence model.” We should be able to articulate which logic we believe applies in a given situation, with reference to evidence.

Second, building a thick understanding of personal and national histories can yield great dividends. Putin’s well-known background as a KGB officer, stationed in Dresden as the Soviet Empire teetered and East German citizens overran the Stasi headquarters, are touchstones in his worldview. The fact that Xi Jinping spent his adolescence in privation, digging ditches and living in a cave in rural central China after party purges and the Cultural Revolution shattered his family has bearing on his belief in the resiliency of the Chinese nation and the need for order. Recent comments in a New Yorker profile by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on why the war in Ukraine strikes such a deep chord are similarly illuminating:

But, when it came to the subject of the war itself, and why Biden has staked so much on helping Ukraine fight it, Sullivan struck an unusually impassioned note. “As a child of the eighties and ‘Rocky’ and ‘Red Dawn,’ I believe in freedom fighters and I believe in righteous causes, and I believe the Ukrainians have one,” he said. “There are very few conflicts that I have seen—maybe none—in the post-Cold War era . . . where there’s such a clear good guy and bad guy. And we’re on the side of the good guy, and we have to do a lot for that person.”

Unpacking these comments can devolve into questionable armchair psychology, but personal frames of reference clearly do matter and shape the depth of our commitments. These personal histories are embedded and informed by broader national experiences (victory / defeat in the Cold War; resilience in the face of chaotic political upheaval) that also demand interrogation.

Finally, we should strive to periodically carbon date our views — reflecting upon when, where, and from whom we learned about people, issues, and situations. This is especially important for generalists, who may acquire deep knowledge of a subject in a particular moment but cannot follow it afterwards due to the nature of their responsibilities.

In my career, I’ve seen several instances where leaders’ views were fixed in earlier moments in time that were less relevant to an evolving situation. To use one example, I once attended a public event with some former officials who were sophisticated supporters of the invasion of Iraq. One of them recognized that they had held a flawed assumptions about Iraqi civil society and government capacity, assuming that re-establishing a functional state after Saddam Hussein’s removal would be vastly easier than it was. The views of some of these policymakers were fixed in time, conditioned perhaps by the claims of exiles but also informed by a vision of Iraq that hadn’t been so thoroughly Ba’ath-ified, purged, and polarized by a murderous dictator in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s.

To use another example, I can vividly recall conversations about the Syrian Civil War where sophisticated individuals would support policies that were based on the premises of 2011 or 2015 rather than 2017 — by which point the composition of the opposition and the balance of forces in the field had changed dramatically. The window of opportunity for certain groups to take on Assad (let alone ISIS) had passed as attrition, exile, and the influx of new forces took their toll, leaving a smaller range of viable options. Knowledge — and assumptions based upon it — has a half-life.

In 2024, we face the prospects of a widening regional war in the Middle East, heightened cross-strait tensions in the Western Pacific, leaps in emerging technologies, and political shocks as populations around the world vote in critical elections in Taiwan, Pakistan, Indonesia, India, Mexico, and the United States, among others.

Whether historian, policymaker, or citizen, we will all be acting and interpreting these events based on “unspoken assumptions” we rarely think about. Best to think about them now.

[1] Joll’s lecture – a brief 22 pages – is somewhat difficult to track down. The most accessible place to find it is in the first edition of H.W. Koch’s edited volume, The Origins of the First World War (London: Macmillan,1972).

[2] Rhode suggests that advertising and humor are also promising “because they function through appealing to the preoccupations and assumptions that their audience takes for granted.” As he notes, they are unusually culturally specific.

[3] Logevall’s argument is worth unpacking, of course. The decision to escalate in Vietnam was a choice but, as with 1914 when leaders felt robbed of agency by external forces and primordial incentives they could not control, the motives outlined in the book are so deep-seated that it is at times difficult to envision how LBJ could have overcome them.

I find the idea of “carbon-dating” our views particularly interesting. As the world evolves, we must update our mental model of the most important causal forces to keep up with the events and to retain some ability to prepare for the future.