Conspicuous Consumption: January 26, 2024

Hofstadter, "Ukraine's War of Narratives," De Palma, Wes Montgomery, Karl Barth

“Conspicuous Consumption” is a bimonthly list of recommendations, drawn from my recent encounters with books, films, music, podcasts, and policy work, and whatever else catches my attention and needs to be digested and shared. Links are provided where relevant. Feel free to leave your own recommendations and thoughts in the comments.

Reading

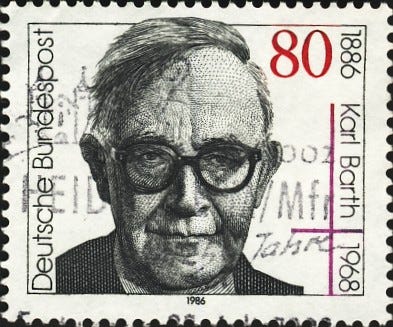

Richard Hofstadter, The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It (1948)

Hofstadter, the prolific historian and public intellectual who twice won the Pulitzer Prize, offers a series of compelling profiles of great American political leaders from the Founders to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Not all of the essays hold up to the scrutiny of later historians, but it’s hard to resist his wit and erudition. The portraits of John Calhoun (“the Marx of the Master Class”), Theodore Roosevelt (“the intellectual fiber of a muscular and combative Polonius”), Wilson (“the essential isolation of Woodrow Wilson was always preserved”), Hoover (what ruined him was “not a sudden failure in personal capacity but the collapse of the world that had produced him and shaped his philosophy”), and FDR (“Hoover lacked motion; Roosevelt lacked direction”) are well drawn and often quite funny. The contrast he draws between Wilson and FDR is particularly thought-provoking and might warrant a future Battle Hymns essay.

Neil Hauer, “Ukraine’s War of Narratives,” War on the Rocks, January 18, 2024

Hauer, a Canadian journalist based in Armenia, provides a coherent account of the “script flipping” that has characterized the Russo-Ukrainian War since February 2022, identifying major narrative swings over whether Russia or Ukraine had the upper hand. These swings were largely based on dramatic moments on the battlefield and amplified through the news media and especially on social media, where nuanced observations filled with caveats are routinely drowned out by boosterism and sensationalism. As the war shifts further towards attrition, with a focus on the inherently less dramatic and visible questions of recruitment numbers, shell production, air defense magazine depth, and economic support packages, he speculates that the twists may come at a slower pace. But they will still keep coming with so much left unsettled.

Watching

De Palma, dir. Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow (2015)

Most directors are lucky if they are able to make one truly great film. Brian De Palma has made several, from Carrie (1976) and Scarface (1983) to Carlito’s Way (1993), Mission Impossible (1996), and, my personal favorite, The Untouchables (1987). This film-by-film look at his career, built around an interview of the irascible man himself, shows you his range, technique, and preoccupations with filmmaking as an art — and the experiments, flops, and personal drama along the way (like the time he tailed his cheating father on the way to a tryst and confronted him, camera in hand). De Palma’s deeper, disturbing, and more torrid cuts reveal him as a worthy successor to Alfred Hitchcock: try Blow Out (1981) featuring John Travolta as a movie sound effects specialist who accidentally records a political assassination . Streaming on Max.

Listening

Wes Montgomery’s Jazz Guitar

Working to music is a mixed proposition. Sometimes it’s impossible for me to get anything done (or at least get anything started) while listening to music. At other times, it’s essential — but then, there’s the question of what to put on and whether it will help you get words on the page. When it comes to jazz, I’ve found myself rediscovering the guitar work of Wes Montgomery (1923-1968) who swings comfortably between hard bop and a smoother, cooler sound — but always using his famous “hitchhiker’s thumb” (his style is well illustrated here by Rick Beato) — to be great listening at the desk. The classic albums are The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery (1959), and the live recordings Full House (1962), Smoking’ at the Half Note (1965), and Live in Paris, 1965 (1965). Try “West Coast Blues” and “Four on Six.”

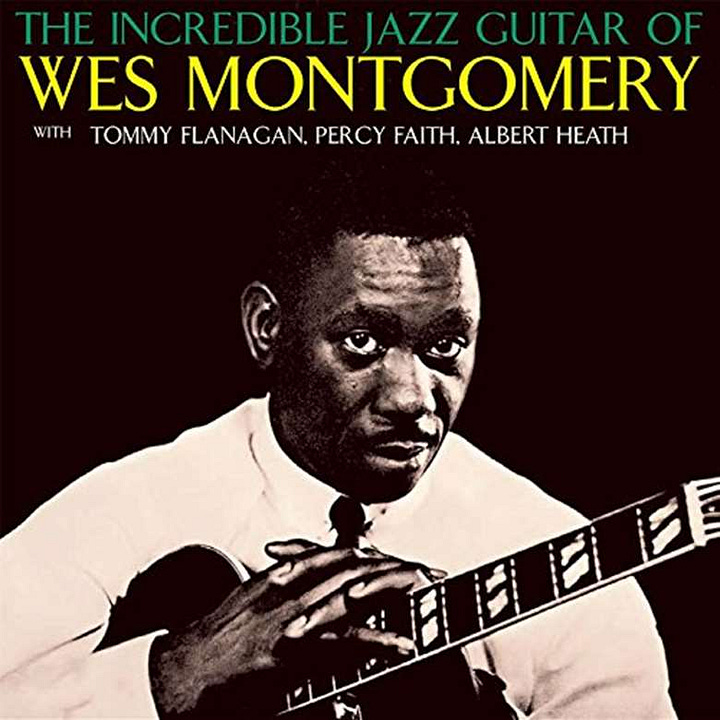

Melvyn Bragg, In Our Time: Karl Barth (2023), BBC 4

The Swiss Reformed theologian Karl Barth (1886-1968) led a remarkable life. He produced groundbreaking commentary in his short The Epistle to the Romans (1921) and very long the 14-volume Church Dogmatics. He broke with the prevailing liberal theology of his day, which he believed elevated Man above God and had served as a handmaiden of the German nationalism that had spurred World War I. Yet he also argued against biblical inerrancy: for Barth, Jesus Christ was the revelation that the Bible pointed towards — not necessarily the revelation itself. He took a public stand against Nazism as leader of the Confessing Church in Germany (Hitler personally ordered his deportation), and maintained a vexed, imperfect personal life. Melvyn Bragg — host of a brilliantly eclectic BBC podcast series on history, arts, and culture — and his stellar panel breaks down why Barth’s theology matters.

Barth’s famous wit is also showcased to great effect by the panelists, including the following anecdote (quoted from John D. Godsey’s book, which I found via Wyatt Houtz):

After the service in a parish church where Barth had been preaching one Sunday, he was met at the door by a man who greeted him with these words: "Professor Barth, thank you for your sermon. I'm an astronomer, you know, and as far as I am concerned, the whole of Christianity can be summed up by saying, 'Do unto others as you would have others do unto you.'" Barth replied: "Well, I am just a humble theologian, and as far as I am concerned, the whole of astronomy can be summed up by saying, 'Twinkle, twinkle, little star, how I wonder what you are.'"